Project Blue: An incomplete history

A peek behind the scenes, right up until the decision.

Tucsonans might find themselves ringed by data centers in the not-too-distant future.

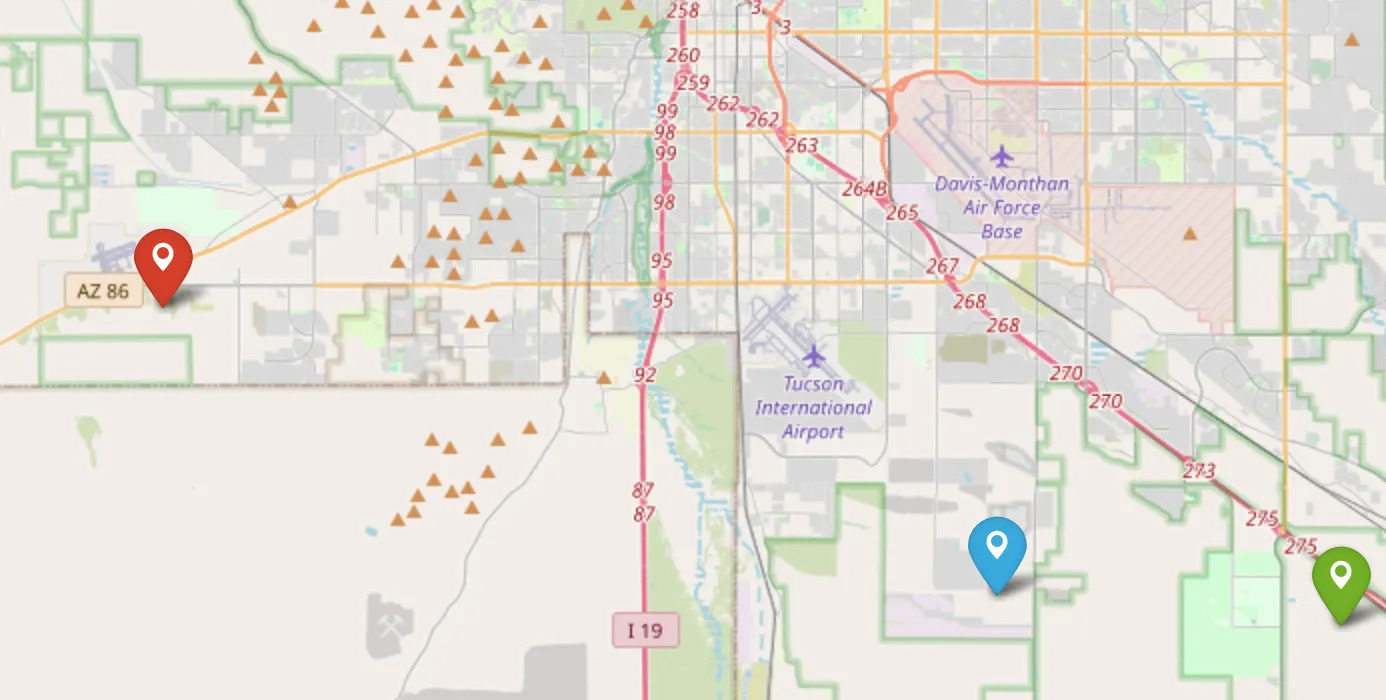

Project Blue is still on the table, even though the Tucson City Council put a big wrench in those plans two months ago. That could lead to a roughly 300-acre data center near the Pima County Fairgrounds.

Davis-Monthan on Tucson’s southeast side is one of five bases where the Trump administration wants to build data centers to help win the AI race.

In Marana, plans are already in motion to build 600 acres of data centers, by the same developer that’s working on Project Blue.

Meanwhile, a 3,000-acre “data center corridor” is in the works in Pinal County.

And those are just the projects we know of so far.

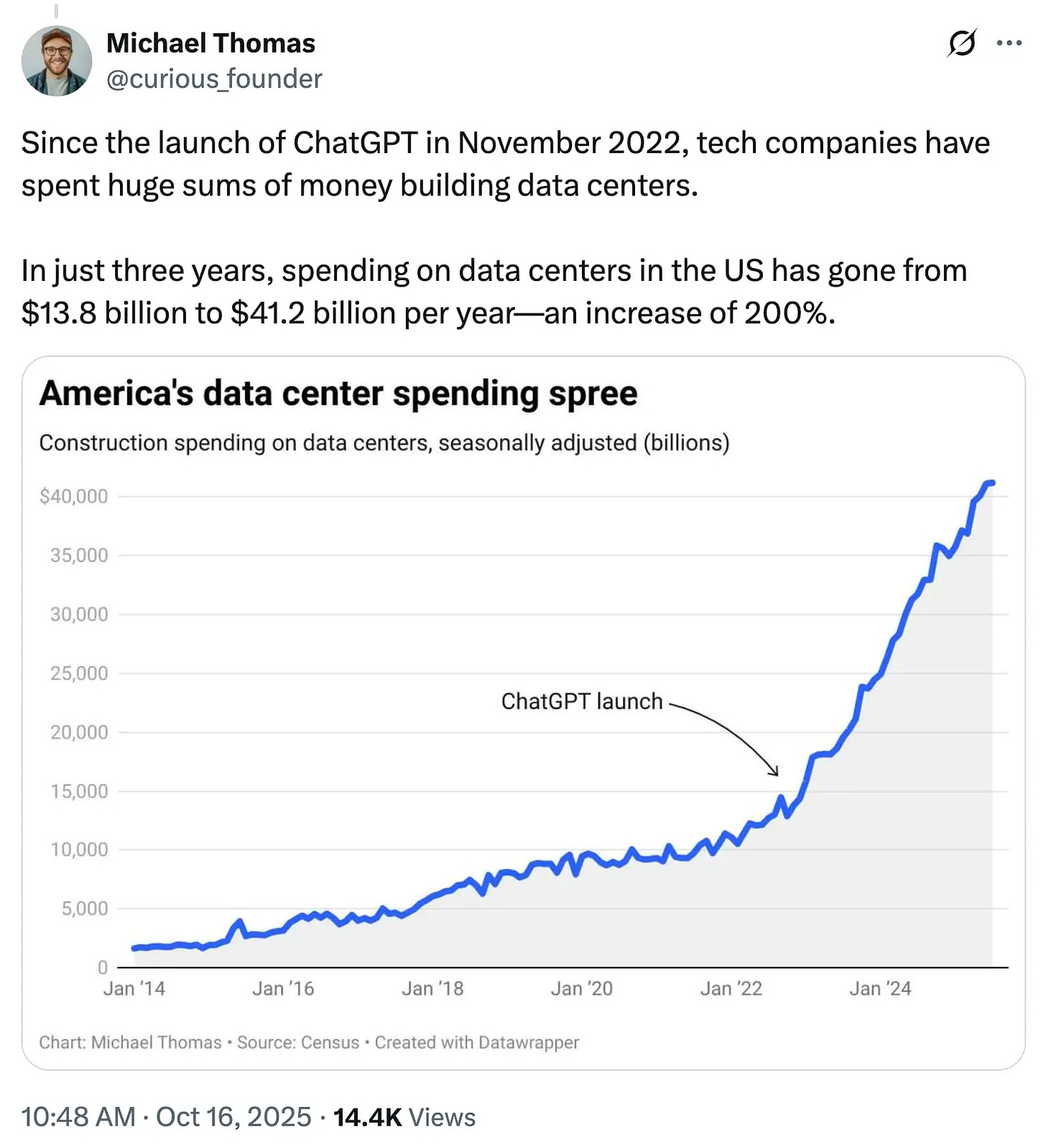

As we saw this summer with Project Blue, data centers are all the rage right now. But getting them built is a long, complex process.

Companies put up big dollars to win a piece of the trillion-dollar AI pie, while local residents worry about straining the power grid (which leads to costly electric bills) and threats to water supplies.

If that weren’t enough, the stakes also include the future of the internet itself. Without more data centers, you can expect repeats of the havoc we saw this week when Amazon Web Services went down.

The game is huge, and Tucsonans are right in the middle of it.

And that means everybody has to stay as informed as possible.

To that end, today we’re going to walk you through several years of public records from Project Blue.

This isn’t a breathless account of scandalous revelations. It’s actually far more important, in its own way. It’s a chance to step back, look at the big picture, and watch how local officials act when data center companies come calling.

So, pour yourself a cup of coffee and let us guide you through the inner workings of how your local government officials handled Project Blue.

If the wave of local data center projects is any indication, this won’t be the last time they have to do it.

Want to surf that wave, instead of getting swept away by it? Then click this button.

A trove of Project Blue records

Our records request turned up 417 pages from Pima County — a trove of documents that residents and journalists waited months to get their hands on.

You can find the documents here.

The records released earlier this month provide fresh details and a timeline of when county and city officials became aware of the planned data centers, which Amazon Web Services has sought to build in the greater Tucson region since at least 2022.

Who knew, and when

Before we dive into the timeline, we need to establish two separate groups based on the documents and public statements.

County economic development officials, Pima County administration, and their counterparts at the City of Tucson seemingly have known about Project Blue since 2022 — something Tucson City Manager Tim Thomure confirmed on “The Bill Buckmaster Show” two months ago.

Elected officials learned about Project Blue in early 2025, primarily through memos issued by Pima County Administrator Jan Lesher. There appears to be one outlier — but we’ll come back to that in a minute.

March 2023: The early emails

In March 2023, Deputy County Administrator Carmine DeBonis reached out to Pima County Director of Economic Development Heath Vescovi-Chiordi for information about Project Blue.

The email was sent minutes after DeBonis received a message from Diamond Ventures President David Goldstein. In it, he stated the developer behind Project Blue wanted to buy 1,200 acres from Diamond’s Verano property off of South Wilmot Road.

“They have given me permission to do due diligence with respect to entitlements, annexation, water, etc.,” Goldstein wrote. “I am meeting with Regina and Mike tomorrow. A lot of pieces to the puzzle have to come together to make it work.”

This lines up with Thomure’s statement that the city was aware of Project Blue as early as 2022, and it likely means Goldstein was referring to a meeting with Mayor Regina Romero and then-City Manager Mike Ortega. At the time, Thomure was the deputy city manager.

It is unclear what details Goldstein offered to Ortega and Romero, and those details would have changed over time anyway. At the time, Project Blue said it wanted 1,200 acres — a far cry from the 290 acres it would eventually purchase from the county.

Minutes later, Vescovi-Chiordi responded to DeBonis, offering to write a brief overview of the project so far.

Later that same day, Vescovi-Chiordi sent another email to DeBonis and Lesher, highlighting that the proposal was tied to a non-disclosure agreement.

“Please be advised, the County has entered into an NDA, so discussion among County Staff/Electeds is ok, for all intents and purposes,” Vescovi-Chiordi wrote.

It’s unclear when City of Tucson officials signed a similar NDA with proxies representing Amazon, but the records show Project Blue had been in talks with Diamond Ventures before March 2023.

Another document — an undated, unsigned one-page memo bluntly stating “Project Blue is Amazon Web Services” — adds to the mystery. That memo also listed an ambitious timeline to break ground later in the year.

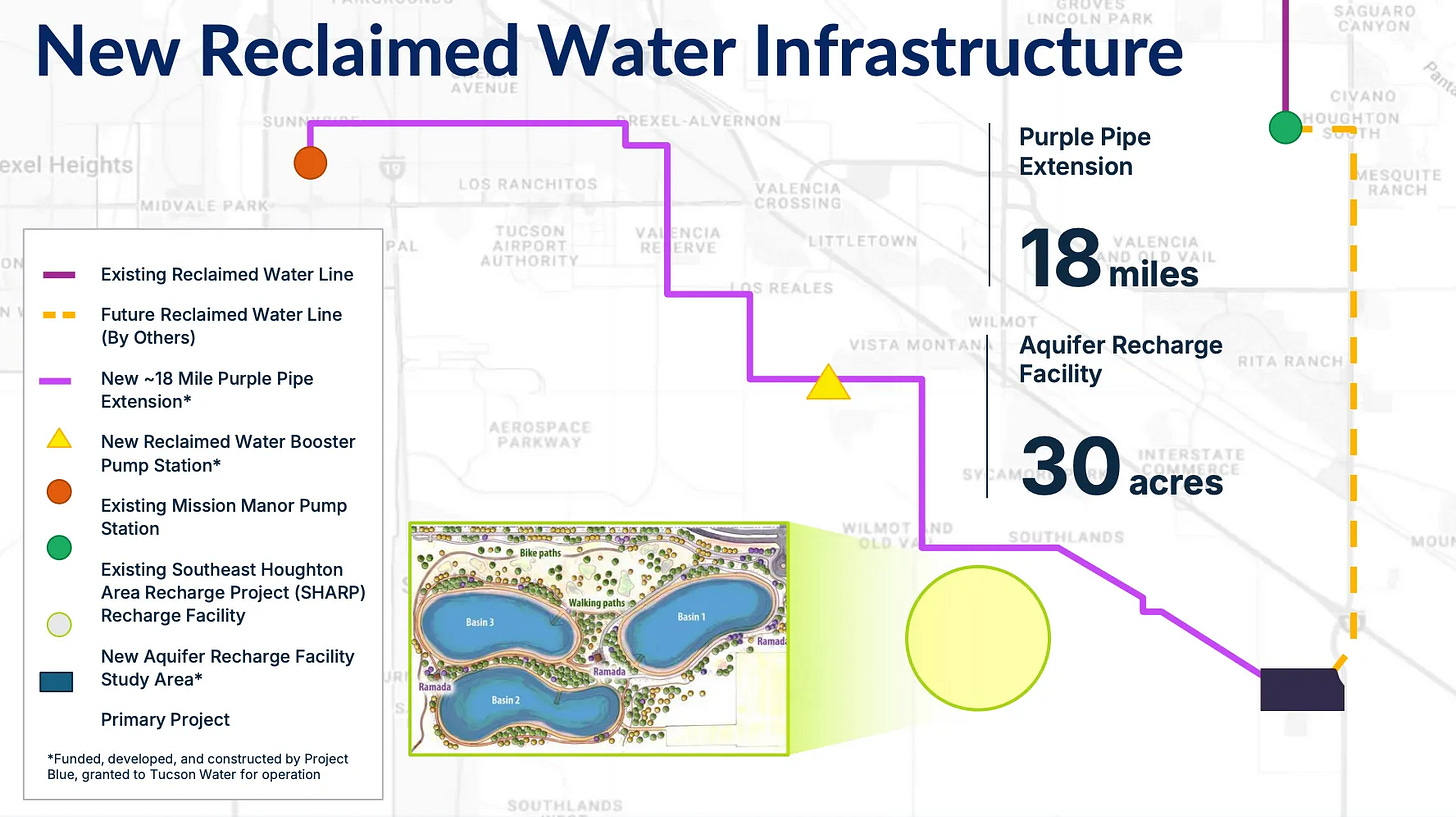

A similar undated memo noted that the planned data centers would need as much as 150 megawatts of power to run the servers and more than 5 million gallons of reclaimed water to cool the facilities at full build-out.

Days later, the Pima County Regional Wastewater Reclamation Department offered three “confidential” possible sites for Project Blue, seemingly as alternatives to the Verano property owned by Diamond Ventures.

This likely connects to a March 29, 2023, email from Deputy County Attorney Sam Brown, who wrote that any property in the county would likely need to be annexed into the city to meet water needs.

That complicated efforts to find a parcel large enough for Project Blue, but also close enough to city limits to make annexation — and therefore water service — possible.

By the end of March 2023, numerous county officials, a handful of city officials, and the president of Diamond Ventures all knew Amazon Web Services wanted to build a massive data center in Tucson.

But nobody from the public or press corps had any clue what the politicians were cooking up.

2024: A new, familiar site

Our records next flash forward to August 2024, when an independent, third-party valuation of the 290-acre county-owned parcel near the Pima County Fairgrounds came in at $20.9 million.

That’s the same site that was later sold in June 2025 to Humphrey’s Peak Properties LLC, a proxy for Amazon.

The report, prepared by CBRE Valuation & Advisory Services, was attached to an email when DeBonis asked the head of economic development for the appraised value.

The 52-page report largely outlines the property and how the appraiser arrived at the figure, though it notes no environmental impact studies were performed as part of the appraisal.

2025: Fast-tracked for the sale

The last time-jump in the documents lands in February 2025, when Lesher began publicly referencing Project Blue — though she described it only as “a company that operates in the advanced and emerging technology industry sector.”

Another memo revealed it was a group of data centers planned for the city’s southeast side.

By May, Lesher said county officials had been working closely with their private-sector economic development partner — still known then as Sun Corridor — on an economic impact estimate.

At the same time, the county was negotiating a sale and purchase contract with Project Blue’s attorneys.

One staff email in May revealed how certain departments were eager to spend the tax revenues generated by Project Blue. At the time, county officials were wrestling with a proposal to create a dedicated revenue source to build affordable housing, eventually settling on a plan to increase property taxes starting in 2026.

“This is over $249M of new tax revenues over 10 years,” the staffer wrote. “This would 100% offset the $250M in affordable housing new property taxes, correct?”

A string of memos flowed out of Lesher’s office in May, offering near-constant updates to the Board of Supervisors about Project Blue.

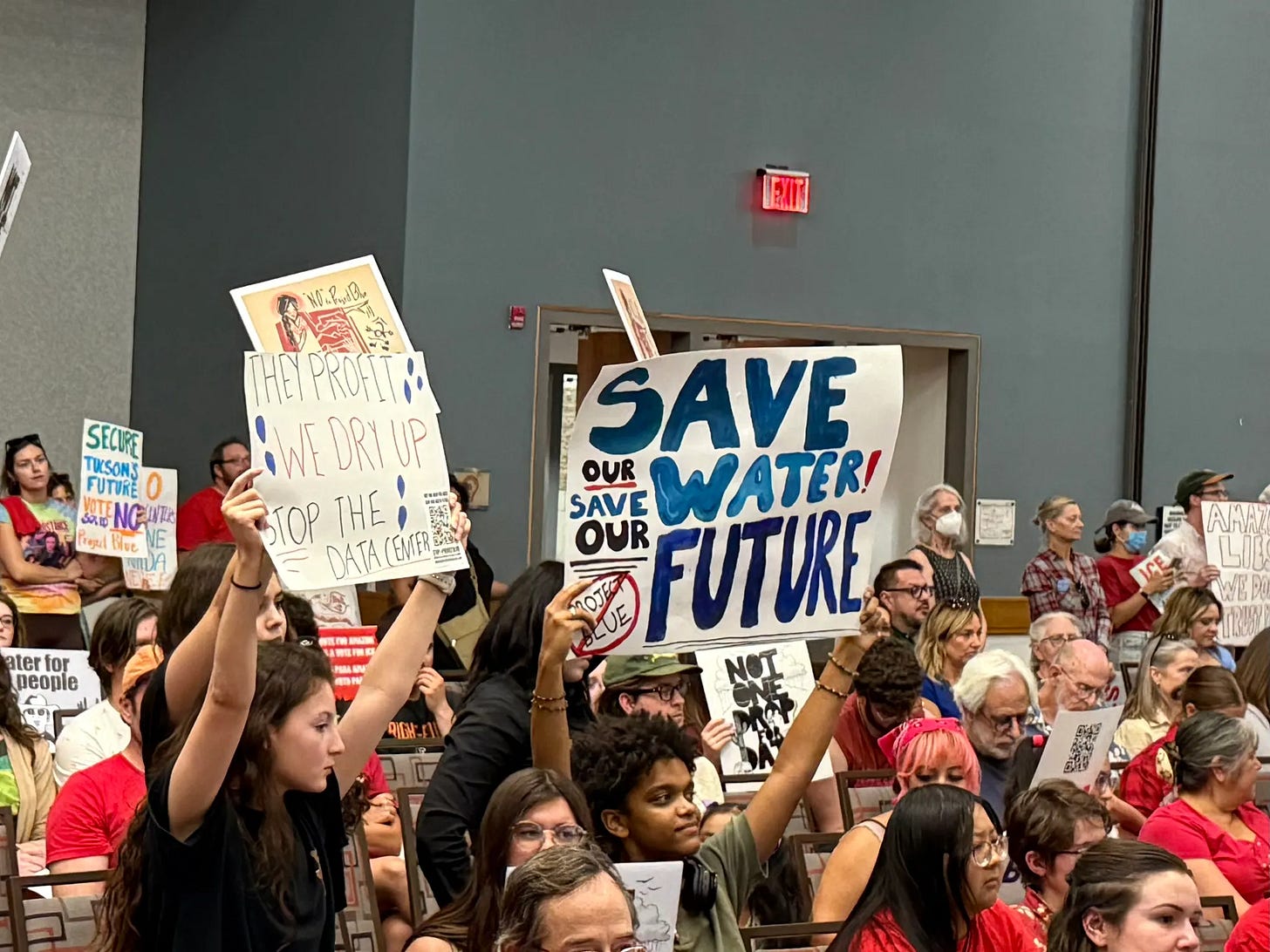

By this point, the public still hadn’t heard of Project Blue and had no idea that their elected leaders had been working on the ultimately unpopular deal for nearly three years.

Behind the fact sheets

An email from local land-use attorney Keri Silvyn — representing Project Blue’s main developer, Beale Infrastructure — shows collaboration with Tucson Electric Power on making a county web page about the data center proposal.

“I made a few minor changes including pulling forward from the fact sheet the water positivity concept. I also understand that the Fact Sheet is being slightly revised today on the energy messaging in conjunction with TEP. Should have revised version soon,” Silvyn said.

In early June, each supervisor met directly with Project Blue’s developers.

Just before the vote

Days before the June 17 vote to sell the land, Lesher, Supervisor Andrés Cano, and staff from other supervisors’ offices met with city officials, including Thomure.

Thomure explained that the developers had agreed to extend reclaimed water lines to areas of the city that lacked infrastructure.

“We wouldn’t have funding for a decade to build out this loop/Southland loop. It is in a growth area and a great spot for reclaimed to be used. But there is no money to build it,” Thomure said.

He also saw an opportunity to move Tucson ahead digitally.

“Having a data center helps with fiber for education and digital literacy. It plays into the County’s fiber ring program and the city’s plan to get fiber to everyone in Tucson. Ring plus city plus data center means we can overcome the digital divide we have,” Thomure told his colleagues.

Supervisor Rex Scott asked for clarification on competing statistics about how many jobs the data centers would create. While Amazon promised 75 direct jobs, total employment — including contracted security and janitorial services — was projected closer to 180.

The county contract, however, could only enforce the smaller number: 75 full-time employees.

A narrow vote, and a rate hike

When supervisors narrowly approved the contract on a 3–2 vote, one staffer suggested county employees who had worked on the project should receive recognition.

On the same day that the supervisors approved the sale, Tucson Electric Power announced it would seek a rate increase — sparking a flurry of emails between the county and the utility.

Lesher called TEP President and CEO Susan Gray that night, seeking assurance that the increase wasn’t tied to Project Blue.

It appears the county was just as caught off guard by the rate hike as the rest of the community.

TEP suggested issuing a joint press release clarifying that the rate increase covered prior improvements. Lesher, however, balked at that idea.

The fallout

We generally know how the story goes from here.

The emails and documents make clear that Project Blue was a closely guarded secret inside the dome of the old Pima County Courthouse and the hallways of Tucson City Hall.

Both the Tucson City Council and Pima County Board of Supervisors have since responded to public criticism of the NDAs — revising their policies and pledging changes to how major economic development cases are handled internally.

It also looks like the public backlash might be shaping how other local officials, not just those at the City of Tucson and Pima County, react when they’re approached about data centers.

Marana officials told KGUN about the new data center projects and walked reporter Madison Thomas through the preliminary details, including ways for the public to get informed and provide feedback. No code names or anything!1

But what about you? The next time Pima County officials consider a data center project, how do you want them to handle it?

What kind of information do you want them to release to the public? Should they hold public meetings immediately?

Let us know in the comments!

Kudos to KGUN’s Madison Thomas for the shoe-leather reporting on this one.

Wow. What a piece. Thank you! Once again our mayor proves capable of backdoor development deals.

Questions: is it really still possible to get out of the county contract with Beale? Was an environmental impact study done? Has the problem of disposing of the E-waste without poisoning our air or water with mercury, cadmium, etc. been looked at?

Thanks for great reporting!!!