Something in the air

One troubling monitor … Prosecute, don’t deport … And the Project Blue petition.

As Tucson focuses on the energy-hungry and water-thirsty aspects of Project Blue, local officials and residents are also raising alarms about a less visible consequence: the region’s worsening air quality.

About a mile from the proposed 290-acre data center site sits a small air-monitoring station operated by Pima County’s Department of Environmental Quality (PDEQ).

It’s one of 15 stations scattered across the county — a simple shed filled with air-quality sensors and equipment, surrounded by a tall metal fence.

PDEQ issued an air pollution alert on July 1 for dust. They also issue other alerts based on poor air quality.These devices measure particulate matter (dust and pollen), carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, and ozone — the latter will be important in a minute — to ensure Pima County is meeting federal air quality standards set by the EPA.

If the county violates those standards for a prolonged period, the EPA could determine that the county is in “non-attainment,” triggering a number of actions to reduce harmful emissions.

Those actions include increased air quality monitoring, stricter enforcement of existing air quality permits, and a long-term plan to reduce overall emissions. The designation could require new businesses moving into Pima County — or existing factories planning to expand — to invest in costly environmental offsets and upgraded air pollution control equipment.

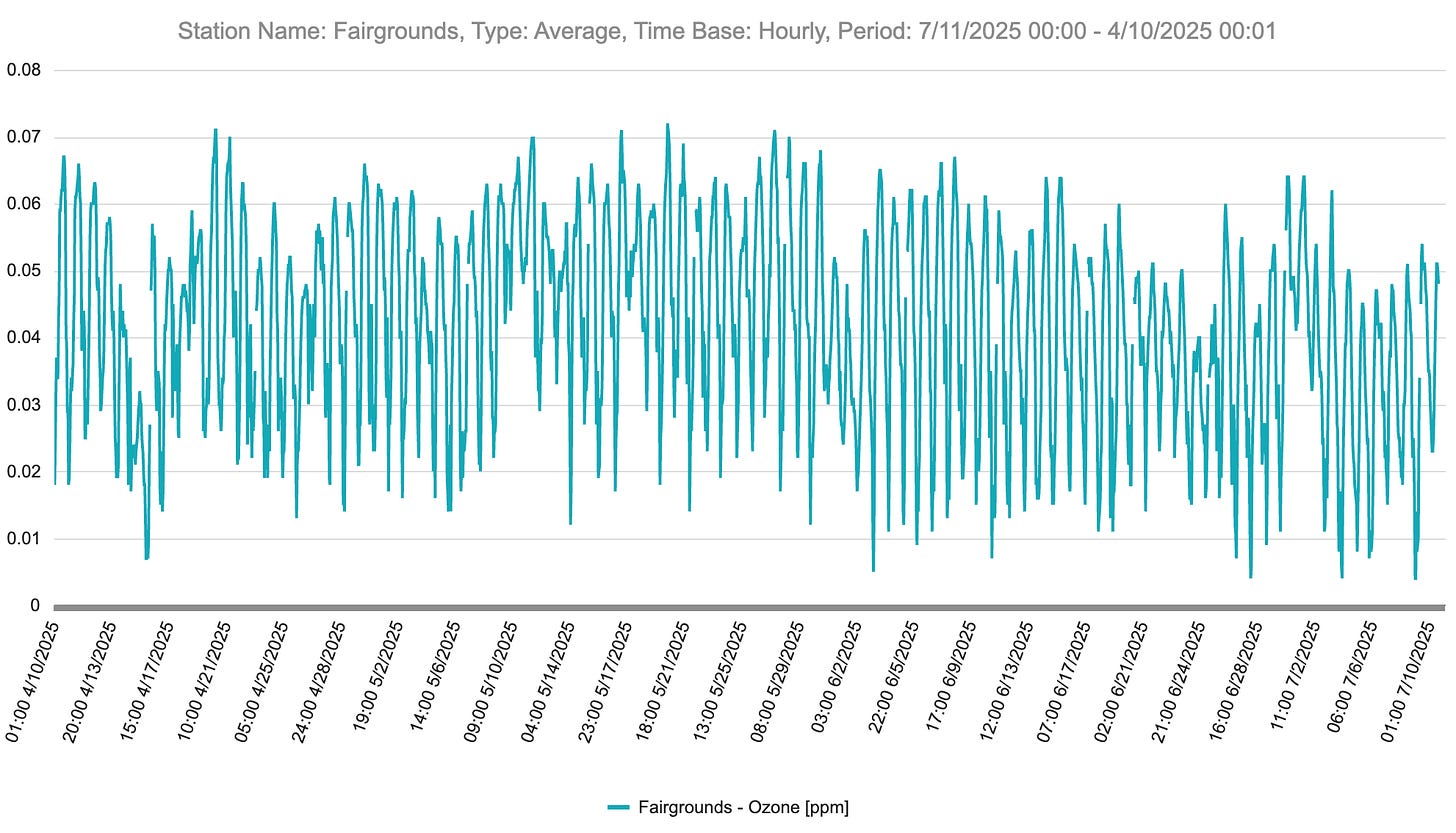

Any guesses which of the 15 monitoring stations occasionally sends out alerts that surface-level ozone is above national standards?

A prize for all of you who guessed the station where Project Blue would be built next door to the Pima County Fairgrounds.

It isn’t all the time, PDEQ Director Scott DiBiase told us — mostly during the summer, due to a mix of environmental and weather conditions.

Ground-level ozone levels peak in summer, with the county's monitoring site occasionally measuring 71 parts per billion (ppb), exceeding the federal standard of 70 ppb.

“During the summertime, the ground level ozone, the smog levels are the highest because of the high temperatures and the abundant sunshine that we have out here,” DiBiase said.

Too much ground-level ozone (also called tropospheric ozone) can lead to respiratory system issues in children, older adults and those who have asthma. Long-term, it can cause permanent lung damage.

Before we go any further, we’ll note that the EPA has labeled Maricopa County as being in non-attainment for ozone for over a decade. It was poised to be reclassified as being in “serious non-attainment” this summer, but the Trump administration has modified ozone guidance so Phoenix companies won’t have to spend millions of dollars on new equipment to offset air pollution.

But just because an administrative policy benchmark isn’t met doesn’t mean the elevated levels aren’t harmful.1

For Project Blue, there are multiple concerns related to air quality:

Project Blue is working with TEP on how to provide dedicated electricity to the power-hungry data centers. A new substation would require a Class 1 air quality permit, which — depending on the technology and energy source — would likely emit a number of pollutants into the air, including volatile organic compounds, particulate matter, and greenhouse gases.

Emergency generators are a fact of life for data centers. The question is how many would be installed — and how often they’d be used. Generators are held to a lower standard when it comes to air quality compared to utilities like TEP.

It would take years for TEP to build a new substation. Environmentalists are concerned about whether TEP will be able to meet its pledge to shut down its two coal-fired plants and become carbon neutral by 2050 if Project Blue adds to local demand.

So while Project Blue could bring in new secondary investments, local companies may also face stricter permitting requirements if regional ozone levels worsen and Pima County is reclassified as non-attainment — a shift local officials say could be accelerated by the large energy needs of users like Project Blue.

Some critics are hoping air quality concerns might be enough to stop Project Blue — but under current permitting laws, that’s just not how it works.

Air quality permits are issued to regulate how much emissions a company can release, but they can’t be used to say “no” based on overall county environmental concerns.

“I had a director, Don Gabrielson, who I worked with and he always had this saying … ‘that air quality regulations are a sad and sorry substitute for proper land use planning,’” he said.

Especially since Pima County is currently in attainment, as far as the EPA is concerned.

In Phoenix, the issue is more nuanced, but new companies have the ability to use emission reduction credits to secure their air quality permits.

With several Tucson City Council members raising air quality concerns, we expect it to be a topic of discussion when the Council takes up the issue in early August.

Until then, breathe easy because you might not be able to in a few years.

Let’s keep Joe on the Project Blue beat until we all know the whole story. Upgrade to a paid subscription today!

Another turf war between the Trump administration and local elected Democrats started earlier this month when federal agents took a first-degree murder suspect out of a Tucson hospital and put him in a federal detention center in another Arizona county.

Pima County Attorney Laura Conover put out a statement saying the move by federal agents, in the middle of the night, was “unprecedented.”

The County Attorney’s Office has had a long-standing relationship with the U.S. Attorney’s Office to mutually decide which office will prosecute when jurisdictions overlap.

In the case of first-degree murder suspect Julio Aguirre, who appears to be in the country without documentation, Conover said it was decided she would prosecute Aguirre.

Her office said there are seven other victims who were attacked or threatened by Aguirre during his hours-long crime spree in Tucson on June 30 that ended with him shooting 69-year-old Ricky E. Miller Sr, who died at the hospital hours later.

“Our case has seven local victims, several more traumatized witnesses, and those who rendered aid,” Conover said in a press release. “To take this suspect away, to score political points about undocumented immigrants with criminal records, and to make our victims wait for years, if ever, to have their day in court, is truly shocking.”

Miller’s son asked that Aguirre remain in local custody, fearing Aguirre will be deported before getting his day in court.

“I said to the Detective more than once, ‘don’t you let him go to the feds. We might not see him again. He could just get deported. My Dad deserves justice first,” he said.

The Water Agenda

It’s hard to pass new water laws in Arizona.

That was cold comfort for 150 families on the Navajo Nation, where a relatively cheap bill would have helped them get running water for the first time.

That bill died in the Legislature, but a much more expansive bill made it through, giving housing developers a tool they’d been trying to get for years.

Those are just two of the dozens of water-related bills that wended their way through the legislative labyrinth of homebuilders, lawmakers, environmentalists, farmers and countless others who have a serious stake in Arizona’s water future.

Hauling water in buckets in the Arizona heat is tough, but it’s still the reality for about one-third of the Navajo Nation.Elsewhere in the never-ending battle over water, Rosemont Copper is poised to move ahead in Oak Flat, the summer heat is taking a toll on fish in Springerville and water rates went up in Nevada, which is bad news for neighborhood trees.

Take a dip in Arizona’s water politics in this week’s edition of the Water Agenda.

The Education Agenda

School may not be in session right now, but the politics of education are still raging, from the Arizona Capitol to the halls of Congress.

Like students, state lawmakers left for summer vacation, but not before two dozen laws they debated this spring were signed into law.

We break down the new rules for you, from how medical schools are supposed to interview applicants, to what will (or won’t) be on school lunch menus this fall.

Our art intern, ChatGPT, thinks (wrongly) that grade-schoolers are going to start betting on sports and taking the SAT.And school choice advocates notched a big win in Congress, although not as big of a win as they hoped.

Meanwhile, Arizona school officials are clamoring to know when they’ll see $118 million in federal money that vanished, right as school districts were finalizing their budgets. And local drama is boiling over at a West Valley district.

Want to get educated on education? Check out this week’s edition of the Education Agenda.

The A.I. Agenda

There’s a tug-of-war going on between states and Congress over who gets to regulate artificial intelligence.

Federal lawmakers were eyeing a 10-year ban on states being able to pass any laws regulating AI, which caused a ruckus among the states. Then the U.S. Senate put the kibosh on that idea last week.

Now, states are kind of like the dog that caught the car. They wanted the job, now they have to deal with the responsibility.

If recent moves by Arizona officials are any indication, they’re going to have to start moving a lot faster if they want to keep up with AI.

Check out this week’s edition of the A.I. Agenda to see how it’s all shaking out.

While you’re at it, get to know one of the key thought leaders (and apparently a really nice guy) behind how we think about AI, and see how ChatGPT is messing with students’ writing, and their brains.

And, of course, we’ve got robots.

Could residents convince the Tucson City Council to reject Project Blue?

It could happen — this Change.org petition already has more than 3,300 signatures.

While we aren’t taking sides on Project Blue, we do have two suggestions for the organizers:

First, leave poor Pima Town Council member Teresa Bailey alone. She’s listed as a decision-maker on the petition. But she had nothing to do with this, and she has enough going on in Gila County.

Also, you’d probably get a little more respect from Tucson City Councilwoman Karin Uhlich if you didn’t list her as a “former Tucson City Council member.” She still has five more months left in her term.

Pima County does have a separate issue with non-attainment related to particulate matter in the area near Marana, but the state is working with local agencies to address that issue.

I'm glad Tucson's ozone issue is being covered. Resolution Copper is at Oak Flat, not Rosemont.

Ozone is also dangerous for athletes, little children and anyone who is running or exercising.

Ozone is highly reactive. Among other things ozone fades dyes and damages plastics.

When exposed to bright sunlight, chemicals in car exhaust react to form ozone. That's one more reason tax breaks on EVs are a good thing.