Secret Santa: A classic from Hank

What I learned from Hank in one story

Good morning, readers!

For my Secret Santa pick, I’m going back to a classic from Hank — a story that sums up exactly what it’s like to work with the guy who founded this thing.

Hank has this uncanny ability to pick up the phone and call the most powerful people in the state and get answers to the hard questions. And he’ll do it in a way that you’d think it was two old friends catching up over coffee. I’ve watched him do it for years and it never gets old.

And honestly? Hank makes the job feel both fun and deeply serious at the same time — like holding power accountable is just a normal part of a Tuesday morning.

Your subscription helps keep that energy alive — the kind of newsroom where we can needle the folks in charge, tell you what’s really going on, and still laugh about it on the walk back to the parking lot.

I struggled with picking my favorite Hank story from 2025. There is an effortlessness in his writing that comes from the deep relationships he has built across both sides of the aisle in the Valley over the last few decades.

There is a quiet confidence in his stories, showing an in-depth understanding of how state politics work and decades of Arizona political history that would easily fill several books.

While I quietly lobby here for Hank to write “Modern Arizona political scandals, Volume 1,” I’ll pivot to one of my favorite stories that shows — not tells — Hank’s ability to unpack a complex political issue while putting it into context.

The headline itself preps you for the answer to the question “Can they do that?” and walks you through the answer, step-by-step.

A rider to the (proposed) renewal of Prop 123 to incorporate vouchers was worthy of some deep reporting in the Education Agenda, but Hank went back to the story to answer whether the Legislature can tack on something to a voter-approved proposition.

At the time, he couldn’t answer it outright as the text of the amendment had not been released. But Hank was clear the Arizona Supreme Court would eventually make the decision. It was the underlying law, the separate amendment clause in the Arizona Constitution, that became the focal point of Hank’s article.

It was fun, informative, and entertaining without feeling like someone was trying to make you eat your vegetables.

I highly recommend reading it.

Let Hank know we want to see more of these explainers by clicking this button.

Can they do that?

Lawmakers are considering a plan to embed protection for Arizona school vouchers into the state constitution by strapping it to a renewal of Prop 123, which provides about $300 million per year in additional money for schools from the state land trust.

We wrote all about it in last week’s edition of the Education Agenda. (Subscribe!) The issue has blown up since then.

But one big question we didn’t address is: Can they do that?

We don’t mean politically. We mean legally.

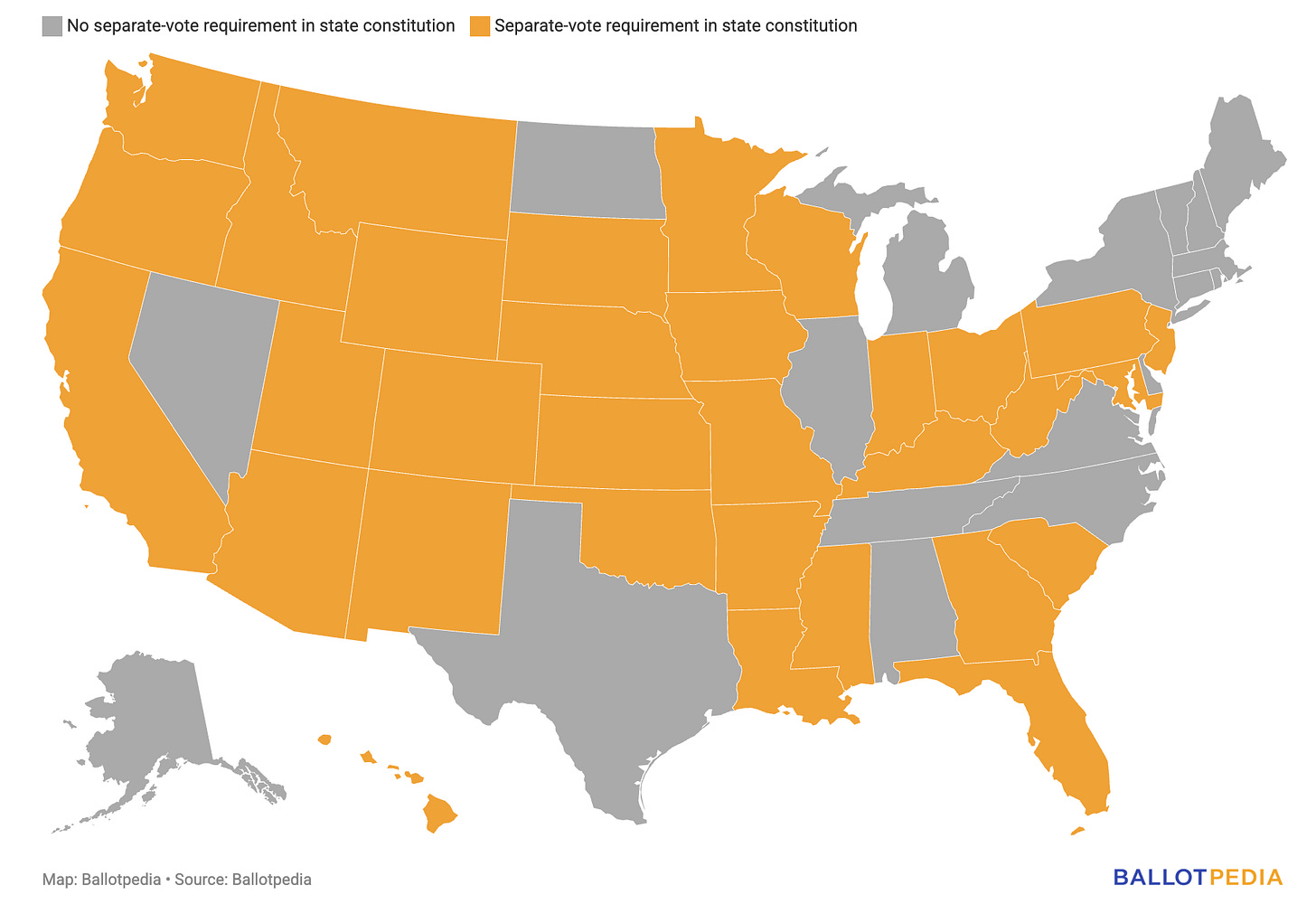

As public education advocates rightly point out, the Arizona Constitution contains a “separate amendment” clause1 that requires any proposed constitutional changes must show up as separate questions on the ballot.

“If more than one proposed (constitutional) amendment shall be submitted at any election, such proposed amendments shall be submitted in such manner that the electors may vote for or against such proposed amendments separately,” the Arizona Constitution reads.

In the last week, we’ve heard from public education boosters who say any attempt to tie vouchers to public school funding is clearly a violation of the separate amendment clause.

And we’ve heard from supporters of the state’s universal voucher program who say the plan definitely doesn’t violate the separate amendment clause.

But lawmakers still haven’t released the text of the amendment that they plan to adopt.

Without that, it’s all guesswork.

And whether the specific amendment that they write does or doesn’t violate that section of the Constitution is above our pay grade anyway — it’s a question for the justices on the Arizona Supreme Court. And we imagine they’ll have to answer it eventually.

But for today, we want to break down what the provision means, how it’s been interpreted over the years and what implications this has for the Prop 123/voucher battle — so that you, dear reader, can be the know-it-all at your next political/education themed dinner party.

Arizona’s founding fathers included the separate amendment clause in the original draft of the state Constitution in order to prevent “logrolling.”

Logrolling is essentially the art of including a popular provision in a bill that is otherwise unpopular. That forces voters to choose between holding their noses and voting for the parts they don’t like in order to get the parts they do like, or voting against something they like in order to stop something they don’t like.

Most state constitutions have some version of the separate amendment provision.

But each state approaches it differently based on the exact language of its separate amendment clause and how it has been interpreted by the courts.

So how do you know if something is one amendment or multiple amendments?

It seems like a pretty straightforward question hinging on the definition of “one.”

But it’s never that simple.

Is it one amendment if it’s all one sentence? How about if the amendment only touches one specific section of the Constitution? What if it’s multiple provisions all on the same topic?

The courts have essentially established that whether “one” means “one” is dependent on all of that and more.

The underpinning of our legal understanding of what constitutes a separate amendment comes from a 1934 case called Kerby v. Luhrs. The case was, somewhat predictably for the time, about taxes on copper mines.

But even the justice opining in that case, Alfred C. Lockwood, acknowledged that the definition of “one” can be more confusing than it sounds.

“There is and can be no disagreement as to the evil the constitutional provision was intended to prevent, and many states, recognizing that evil, have adopted provisions in their Constitution like ours in order to prevent it,” he wrote, referencing logrolling as the evil practice.

“The difficult question, however, is to determine what test shall be used to ascertain whether there are in reality several amendments submitted under the guise of one.”

Lockwood turned to other states that had wrangled with the problem and found a pretty consistent principle, if not a consistent application of that principle.

He tried to restate the collective wisdom as simply as judges in his day could.

Single Amendment:

“If the different changes contained in the proposed amendment all cover matters necessary to be dealt with in some manner, in order that the Constitution, as amended, shall constitute a consistent and workable whole on the general topic embraced in that part which is amended, and if, logically speaking, they should stand or fall as a whole, then there is but one amendment submitted.”

Multiple Amendments:

“But, if any one of the propositions, although not directly contradicting the others, does not refer to such matters, or if it is not such that the voter supporting it would reasonably be expected to support the principle of the others, then there are in reality two or more amendments to be submitted, and the proposed amendment falls within the constitutional prohibition.”

Notice that bolded part there. Lockwood is saying that two ideas that a reasonable voter would find in conflict — like, say, public dollars for private schools versus more money for public schools — cannot be a single amendment.

Under that interpretation, it’s probably safe to say most reasonable voters would find a combination of private school voucher protections and public school funding to be competing — meaning they would support one or the other, but not both.

So slam dunk, right?

Nope.

Fast forward almost 75 years.

In 2006, the Arizona Supreme Court again returned to the question of what constitutes a separate amendment.2

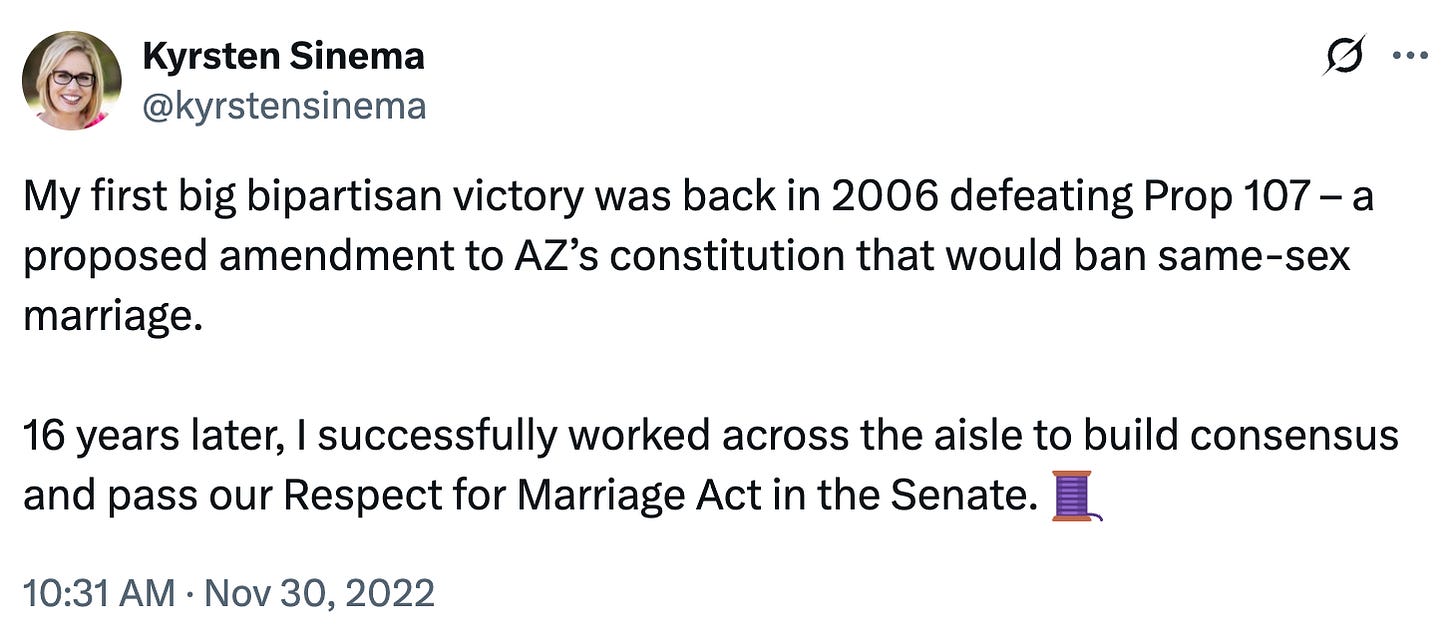

This time, it was about gay marriage in a case called Arizona Together v. Brewer.

Anti-gay groups had proposed a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage called Prop 107. LGBTQ+ groups argued that it was actually three amendments: To ban gay marriage, prohibit civil unions and prohibit the government from awarding benefits and rights to domestic partners.

And they argued, based on polling at the time, that a “reasonable voter” wouldn’t support all three — they may have been in favor of banning gay marriage, but not for barring civil unions and rights for domestic partners.

The court not only rejected that argument, it struck down the whole “reasonable voter” doctrine, saying judges shouldn’t have to speculate about what voters want and there are better ways to determine whether one amendment is actually many.

“(L)itigants have persistently attacked proposed amendments under the reasonable voter approach by using a variety of arguments, most of which asked the Court to speculate about the behavior of the electorate at some future time,” the justices wrote in their decision.

Instead, the court went back to a “topicality and interrelatedness” test. Essentially, do they touch on the same topic? And is one provision logically and reasonably related to the other, even if the two provisions are not actually dependent on one another.

In essence, the court stopped asking the question: “Would a reasonable voter view this as logrolling?”

The Arizona Supreme Court allowed that 2006 constitutional ban on gay marriage (and civil unions and rights for domestic partners) to go to the ballot.

Former U.S. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema chaired the campaign against it, and she writes about the episode in her book, “Unite and Conquer.” The key to their success, she writes, was not focusing on the gay marriage ban, but on the implications for straight people and domestic partners.

“Our campaign message was unique (as was most of the campaign, really). We focused on the impact that the initiative would have on unmarried couples in the state, rather than fighting with the proponents about the merits of same-sex marriage,” she wrote.

Voters ultimately rejected the constitutional amendment, which was kind of an amazing moment, considering gay marriage bans were still pretty popular back then.

What Sinema doesn’t talk about in her book is that, two years later, anti-LGBTQ+ forces at the Capitol went back to the ballot with a more narrowly tailored gay marriage ban that didn’t include civil unions or domestic partnerships.

And voters approved it.3

So what’s the modern-day lesson we should take away from that tale?

Well, while the court stopped questioning whether a regular voter would view a multi-provision constitutional amendment as logrolling, regular voters didn’t.

The separate amendment clause is a lot like the “single subject” rule in the Arizona Constitution, except that it only applies to constitutional changes and it has been interpreted by the courts more strictly than the single subject rule.

Yes, there were lots of cases in between. For simplicity’s sake, we’re not getting into those. This email is long enough already.

That provision in the state Constitution was eventually invalidated by the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. Though it’s technically still in our Constitution.